The Nigerian Soft Drinks Market - What You Need to Know

A few weeks ago, I went into a popular shopping mall to grab a drink to rehydrate after a hectic day and I was spoilt for choice. There were budget and exotic drinks, healthy drinks, locally manufactured yoghurts, home-made drinks, standardised fizzy drinks and foreign drinks on display. Two thoughts ran through my mind as I stood there pondering what to choose. Firstly, the recent government's position on foreign products has had little impact on the wealth of brands available to consumers. Obviously, some of these foreign brands are in partnership with some local distributors. What will they do to continue to have a share of the pie?

I was also impressed by how far indigenous companies have come. I felt the same pride I felt when I saw a “Made in Nigeria” drink in a grocery store in London. Compared to ten years ago, it seems to be an exciting time for customers in the soft drink industry. There are currently over 100 soft drink brands made or bottled in Nigeria from about 15 bottling or drink manufacturers. Two-thirds of these are indigenous Nigerian firms.

However, I could not help but wonder about the fate of some of these indigenous firms ten or twenty years down the line. Looking at our burgeoning population, high humidity and temperature as well as the growth of health-conscious middle-income consumers who recognise the need to maintain rehydration and electrolyte balance; more soft drinks are expected to launch in the coming years.

Will there be more mergers or acquisitions as we saw with Coca-Cola and House of Chi? How well-positioned are our local brands for mergers, acquisitions or even joint venture partnerships? How can these indigenous firms defend their business against new entrants? What can prospective entrants expect? In this piece, I am going to be sharing a few insights new entrants and incumbent companies can draw on to gain traction in the Nigerian drink industry.

Overlook the market size

Nigeria’s population is enticing. But it is more enticing for any manufacturer with a product that targets young people because Nigeria has the youngest population in Africa. However, as a new entrant in the soft drink industry, dwelling on the population size can be a trap. This is because, given the country’s population size, it is very easy to fall into the China Syndrome of thinking “if I can capture 1% of Nigeria’s 200 million people, I will have a market of about 2 million people”. This is an oversimplified view.

No doubt, the population of Nigeria presents a huge opportunity for entrants into the food and drink industry. However, in reality, even companies who market essential products like diapers and female sanitary pads still advertise. At the very least to sway non-customers who are still a viable customer segment. So a better strategy would be to look away from the market size to market segments, their growth rates and unique factors that affect growth in each segment.

At first glance, the market for non-alcoholic drinks otherwise known as soft drinks in Nigeria might seem unstructured. Nevertheless, detailed analysis reveals the following categories:

Fizzy or carbonated drinks

Energy drinks

Drinks for health-conscious consumers

The fizzy drinks refer to carbonated drinks packaged in glass bottles, PET bottles or aluminium cans such as Coke, Sprite and so on. Energy drinks, on the other hand, belong to a class of products in liquid form that typically contains caffeine, with or without other added dietary supplements. One of the most common here is Red Bull Finally, the last segment is healthy drinks. This includes bottled water, yoghurt and most fruit drinks.

As a new or prospective entrant, it is important from the onset to determine what segment to play in. This is because, from a profitability point of view, the more standardised segments like the fizzy drink segment are saturated and dominated by entrenched players who have not only perfected their packaging and distribution channels, but can easily meet some of the best practices in the industry. Some of these best practices or minimum standards expected from new entrants coming into the market are in reality subtle entry barriers. Even when new entrants scale these barriers, they may find the opportunity for product differentiation very limited. This forces them to compete on price alone, leading to consumer surpluses which benefits consumers alone. The obvious implication of this is that the Fizzy segment might not be as profitable as it looks.

Beyond profitability and returns, it is also important to understand the market segments because demand and growth rate of each segment are not the same. For example, there are clear indications that demand in the fizzy sector has slowed down. The energy drink segment, though viable and less saturated is subject to medical scrutiny. So the most viable segment logically seems to be the healthy drinks category. The former observation is validated by the fact that Seven-up Bottling Company, a major player in the fizzy sector recently pulled out of the Nigerian Stock Exchange after posting losses for two consecutive years while the latter is validated by Coca-Cola’s recent acquisition of Chi, a leader in the production and distribution of healthy drinks in Nigeria.

Finally, segmentation is important for reasons relating to pricing, packaging and the actual volume of your product, very important metrics as we shall see. For example, packaging, volume and price in the energy drink and healthy drink segment are heterogeneous. So producers can differentiate their products. Nevertheless, these segments compete heavily with substitutes like alcohol and local products. Moreover, there are few entry barriers in these segments. So while growth rate might be high, it is important not to underestimate local competition. As a new entrant targeting the health-conscious middle-income families for instance, it is important to understand how a local product can affect you. To have a competitor who has invested less in production, regulatory compliance, packaging, distribution and marketing yet has a good geographical spread can impact the long term profitability of your business.

A typical example is Zobo, a popular drink made from Hibiscus leaves in ginger flavour. Because it is home-made and sold locally, it is available in virtually all parts of Nigeria. Yet there are no regulatory requirements as the purchase is solely dependent on the buyer’s discretion. Also, because it is often packaged in recycled PET bottles, the cost of packaging is low. One way to beat such a competitor is to adjust the price and volume of your product to give consumers more value. But while adjusting price and volume can be used to defend your business against local competition, it is counterproductive against competitors who have a similar cost structure.

Avoid the price-volume trap

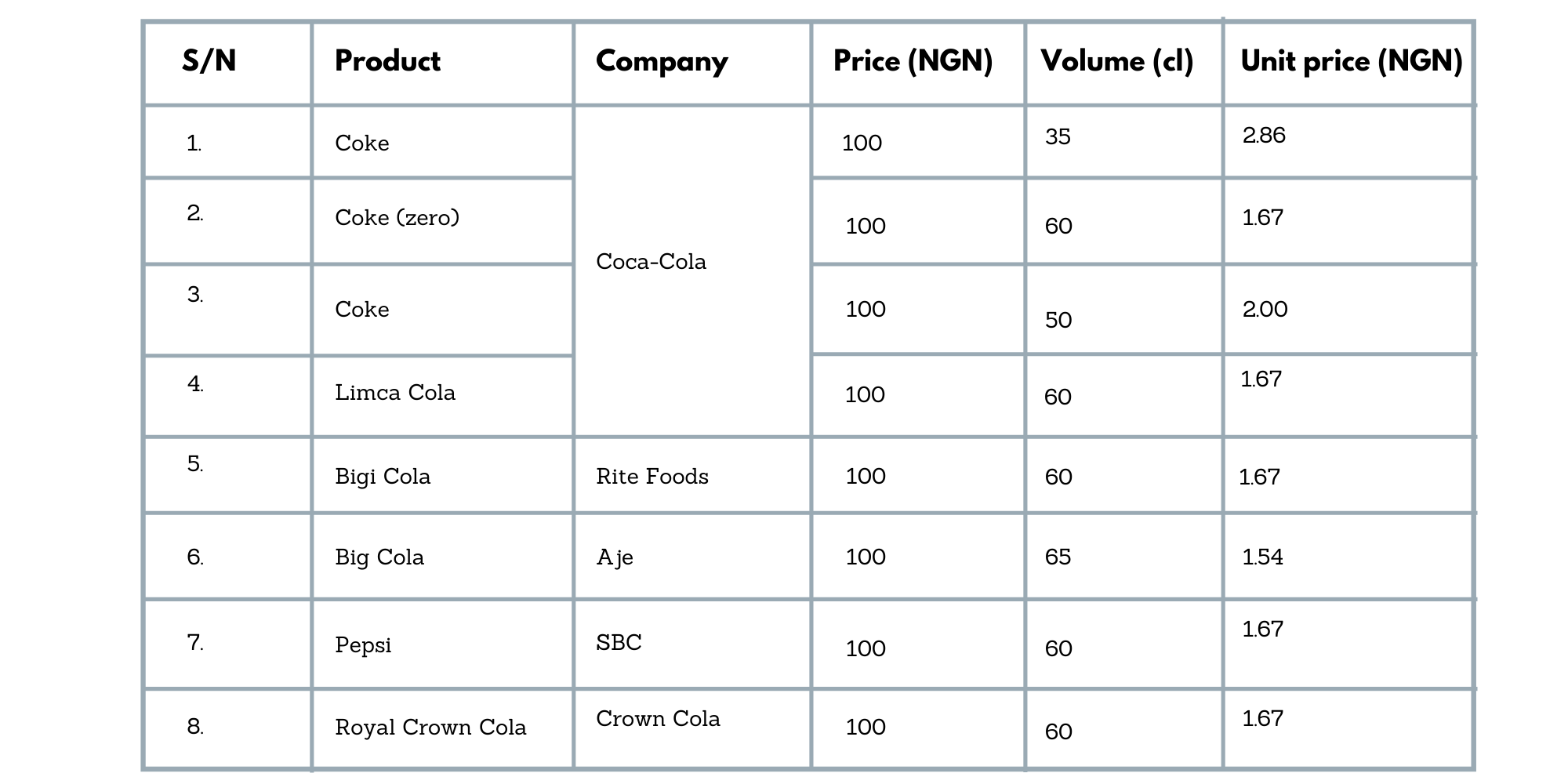

Several articles have been written on the impact of new entrants on Coca-Cola’s dominance in the fizzy drink market. However, a close analysis reveals that most of the strategies adopted by these new entrants border on price reduction or volume increase. This is unsurprising. It is generally said that Nigerians are price sensitive and love giveaways. Consequently, most new entrants focus on price and volume. For instance, the nett effect of the entrance of new competitors like Rite Food, Royal Crown Cola and Aje East into the fizzy drink market has been to increase the average volume of most carbonated drinks to 60cl and push the industry price benchmark to NGN 1.67 per cl. The Table below captures details of some of the most common products in the Nigerian market.

Soft Drinks Price-Volume Comparison

Looking at the table, although Coca-Cola sells above the industry benchmark price, it launched Limca Cola at the new benchmark in 2018. Showing that they are not completely oblivious to competitors’ strategy.

There are two lessons new and prospective entrants must learn from this. The first is that there are not only concerns about profit margin (discussed in the previous section), there is also a price cap. In other words, it will be hard for a new entrant to sell above the industry benchmark price of N1.66 per cl and expect the same results as Coca-Cola. In addition, please be aware that NGN 1.66 per cl is not very enticing given the high cost of production and distribution in Nigeria.

The second lesson can be seen by comparing Coca-Cola’s 35cl bottle with Big Cola’s 65cl. Because Aje’s Big Cola has the highest volume, it also has the lowest unit price of all the products under review. The simple implication is this. Since most of these drinks are targeted at customers “on the go” and not families, it is very unlikely for a new entrant to increase the volume beyond the 60/65cl limit. This means increasing your volume beyond a certain level impacts your profit margin. Especially when the price is capped by competitive forces.

To sum up, recognising that customers want more volume is important. But it is equally important to understand that when there are price restrictions, further increases in volume will affect your margin. No doubt, the price-volume trap is more pronounced in the fizzy segment at the moment. However, competition and standardisation will produce a similar effect in other segments. So it is important to avoid competing on these factors or to identify new ways to offer more volume without price restrictions or vice versa. This will be discussed in subsequent sections.

Learn from local bottled water companies

Given the size of Nigeria, it is not easy for any single player to achieve total dominance. This is because growing beyond a certain size can overstretch resources as distribution costs become very high in the face of local competition. This is best demonstrated in the bottled water industry where, in spite of the presence of multinationals like Nestle and Pepsico, there is no market leader. This is because of the presence of a lot of local competitors with coverage per locality efficiency over the regionally focused-multinationals.

The point here is this. You can not adopt a regional strategy and expect to beat a local competitor in their stronghold. To buttress this point, let us imagine a hypothetical new entrant WaterLite, looking to enter the water sector in Nigeria. Assume that WaterLite decides to focus on ten or five cities in Nigeria. She will face several operational issues as well as competition from both foreign and local competitors, most of whom have no plans of expanding their business beyond that location so can afford to defend their territory. Because they are closer to customers, they would understand the territory and have certain advantages like short delivery times. This could be the reason a product like Cascade might be selling more per their capacity than Eva and Pure Life on Lagos Island. Conversely, if on the other hand, WaterLite focused its business in a well-populated city like Lagos alone (like many local players), it could be more aggressive in the execution of its strategy. This is the strategy adopted by Sabmiller with Hero beer which has a stronghold in South-East Nigeria.

What lessons can a new entrant or incumbent learn from this? While it is tempting to be a national hero, it is much better to expand on success than to contrast on failure. So stay focused on a location that resonates the value you want to portray.

A reasonable profit margin to retailers might trump advertisement

Many multinationals spend fortunes on advertisement most times using renowned global sporting heroes and taking advantage of sporting or social events. While this could influence some consumers, be aware that in a multi-cultural context, this might not be the most crucial swaying factor. And you might not have the luxury of making context-specific advertisements. So most times, at the time of purchase, the decision to buy or not to buy could border on other local factors like price, weather and most importantly availability and persuasion. In other words, for some consumers, it is a case of “when the desired is not available, the available becomes the desired” while for others it is that recommendation or persuasion from the key seller.

So another important factor to take into account is whether retailers are happy with the price of your bulk product or bundle since the availability of your product can depend on the profit margin accruable to the retailers. For example, La Casera apple drink is rarely seen in most formal eateries or other popular outlets. Yet, it is one of the most popular drinks in Nigeria. This it owes to hawkers who hawk them religiously in traffic, motor parks and several public places. If you have ever been in traffic in Nigeria chances are you should have seen La Casera. Nevertheless, La Casera’s popularity with hawkers might be down to the profit margin accruable to retailers. A similar tactic was adopted by Bigi Cola. So when considering your tactics, it is important not to ignore the persuasive power of your distributors.

Stay aware of regulations and how it can affect you in the future

Packaging is key in the soft drink industry not only for branding purposes but also for cost, durability and longevity of your product. The most common soft drinks packages are PET plastic bottles, paper cartons, pouches, aluminium cans and glass bottles. Amongst these, the most widespread for soft drinks is PET plastic bottles. However, with the growing sustainability concerns about product packaging, new entrants need to think about how to deliver their product.

Of all the packaging alternatives outlined above PET bottles seem to be drawing more negative publicity. Globally, the McAuthur’s foundation is leading the race for a plastic-free planet and has asked all major drink manufacturers to report their plastic footprint. Since PET bottle’s popularity is down to its low cost and adaptability, the industry is set for some huge shifts if PET bottles are banned in Nigeria like in some parts of the world.

To this end, it is good to consider other viable alternatives. The most common alternatives are glass bottle, carton papers and aluminium cans. Undoubtedly, from a cost standpoint, PET is ideal. However, the table* below highlights other important metrics which shows it would not be easy to adopt wide-scale changes. For instance, while glass and PET bottles have similar environmental or energy footprints, compared to PET bottles, the liability for recycling glass bottles lies with the manufacturer since the value the customer gets is the liquid content only. This was initially the reason for the widespread adoption of PET bottles over glass bottles but now a major factor for its criticism in the face of growing sustainability concerns.

Soft Drinks Packaging Comparison

* The table is an estimate of the impact of these alternatives

To sum up, new entrants should recognise that there could be packaging problems on the horizon and no easy way out. For example, paper packaging might be cheap and have a low footprint, but it can not withstand the pressure of carbonated drinks. Aluminium, on the other hand, has little reuse potential while glass has a high Capex and leaves liability to the manufacturer. Regardless, at the moment, aluminium and PET bottles seem to be the most reasonable alternative. New entrants should make plans to have a mix of aluminium and PET from the onset.

Explore using the Ribena Model in a B2B context

There are several ways to stay ahead, remain sustainable yet deliver value to your customers. No doubt, we have seen that customers want more volume at a cheaper price. We have also pointed out that competing on price and volume would impact the bottom line. I would like to see new entrants experiment with selling concentrates like Ribena.

There are two advantages to the Ribena model. The first one is that it provides customers with more volume at less cost. Nevertheless, it equally gives the manufacturer the freedom to set their price. Since this price is set by the manufacturer, it can be assumed that they are profitable at that rate. This implies that once a manufacturer is satisfied with the profit margin of the concentrate, they can satisfy their customers without the pressure of a price cap like in the fizzy segment. To illustrate, consider the 1.5 litre Ribena concentrate, sold for NGN 2500 in retail outlets. This is equivalent to a unit price of N16.67 per cl, which is far better than the industry benchmark in the fizzy segment. Going by the dilution standard set by the manufacturers, a 1.5-litre concentrate is expected to yield 7.5 litres (750 cl) of the diluted ready-to-drink product. Compared to the 45 cl of the same product sold at a unit price of NGN 6.67 per cl, the concentrate represents a cost saving of about NGN 3.3 per cl to the customer.

The second advantage of this model is that it can help organisations cut down their plastic footprint as it will empower customers to use their own bottles or cups. Nevertheless, not all companies will find the prospect of selling concentrates very exciting. But the Ribena model can also be useful to organisations looking to target new business to business (B2B) opportunities in organisations such as schools, clubs and other social environments where consumption is usually more immediate. We have seen that there are growing concerns about the ultimate disposal of packaging, so changes are expected in the future. Concentrates can be sold in specially designed Soda dispensers, akin to water dispenser cans, which can be refilled. The retail partner then sells at a fixed rate to end-users. The dispensers need little or no electricity to work as the retailer can run the concentrates into ice cubes. Manufacturers can also set up automated dispensers in strategic locations in cities and public places.

This method has several advantages. Firstly, it will put power in the hands of the organisation (such as schools or restaurants). We have discussed how the profit margin accruable to retailers can be crucial in the availability of your product. Secondly, since the dilution ratio is determined by the producer, it can help to avoid the price-volume trap. Finally, owing to the fact that end-users can purchase their drinks in paper cups, this method will meet the most stringent sustainability requirements.

Using the Ribena model in a B2B context can also be useful to producers keen on exploring drink mixing. Drink mixing, that is mixing soft drinks with alcohol is a practice that is gaining wide acceptance today. The objective here is not to give customers more volume but to identify new opportunities for sales. So it might be worthwhile to partner with alcoholic brands that compliment your product’s content.

To sum up, here are the key points reiterated for new entrants into the Nigerian soft drink industry; Firstly, focus on market segments and unique trends that dominate each segment. Secondly, avoid the price-volume trap that cuts profitability and only benefits customers. Rather, pay attention to profit margin accruable to distributors and retailers. Their local knowledge and persuasive skills can go a long way. Fourthly, stay aware of sustainability requirements and how it can affect the packaging of your products. And finally, the Ribena model can go a long way to address sustainability concerns and deliver value to customers without impacting your bottom line.

If you would like to learn more or would like help with Market Entry Analysis, please get in touch with Info@thethreadgroup.com